RRP: £10.95

BINDING: Paperback

PUBLISHED: 1999

ISBN: 9780946162611

PAGES: 128

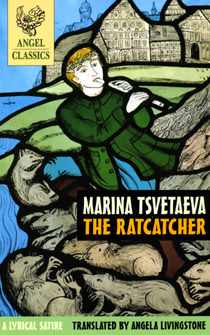

Marina Tsvetaeva

The Ratcatcher: A lyrical satire

Translated from the Russian by Angela Livingstone

This narrative poem, written in the 1920s, is one of the peaks of Tsvetaeva’s oeuvre. Its full text was not published in Russia until the 1990s, and this complete English translation by Angela Livingstone, long associated with 20th-century Russian poetry, Tsvetaeva in particular, brilliantly brings its wild music to the English-speaking world.

Using the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamlyn, the poem pits Art against Philistinism in a critique of all social search for material prosperity. Even for the innovative Tsvetaeva, this is quite a new kind of writing – an explosion of clashing sounds, voices and rhythms, fuelled by anger and bitter sarcasm. The Piper, standing for the magical power of Art, finally takes a terrible toll of the children of the town of Hamelin – neat, comfort-loving, hypocritical and reluctant to pay its debts.

‘This translation is just dazzling; it inspires absolute confidence. I enjoyed and admired it most intensely … I should never have anticipated your skill with the cracklingly concrete, colloquial, immediate, and elliptical brilliance of this piece.’ – Michael Frayn, letter to the translator

‘For the first time we have a readable Tsvetaeva which persuades us that she must have been a very great poet.’ – Lachlan MacKinnon, Times Literary Supplement

‘I think this is the very pinnacle of the art of translation; what translation of poetry should be but rarely is … Angela Livingstone’s version is so close in meaning to the original that I don’t see the liberties playing a major role here. Rhythm, rhyme and the meaning – everything is so much like the original, it’s almost … well, if not supernatural, then superb.’ – Nina Kossman

‘Reading Russian poetry in translation, I often have mixed feelings. The joy of discovery is quickly blotted out by vexation, and after a few dozen lines persistent annoyance sets in … Rarely, it is otherwise. In a finely tuned line of verse in the target language the style of the original begins to tremble with life, the incomparable music of Russian syllabo-tonic poetry, and then the original not only shines through the dense layers of a foreign linguistic element but seems to stand on a level with it, as if two brothers were comparing heights together. The first impulse is then to look at the translator’s name, and next, to go to the original to compare texts and admire the talent – of the poet or the translator? … Of both. This was my experience when this English translation of Tsvetaeva’s Ratcatcher fell into my hands … Hats off to Angela Livingstone!’ – Sergey Nikolaev, Rostov State University

MARINA TSVETAEVA was born in Moscow in 1892, of a father who became famous as the founder of what is now the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts and a pianist mother who wanted her daughter to have the artistic career she herself had renounced. At nineteen she married a member of a family which had been associated with the revolutionary terrorist organisation The People’s Will, by whom she had two daughters, one of whom died of starvation during the Civil War of 1818–20. In May 1922 she left Russia to join her husband, who had served in the White Army, in Prague, where, living in relative poverty and writing constantly – including most of The Ratcatcher – she gave birth to a son. In 1925 she moved with her son to Paris, where she completed and published The Ratcatcher. She returned to Russia with her son in 1939, at the height of the purges, to rejoin her husband who, unknown to her, had begun to work for the NKVD. Her sister, who had not emigrated, had been arrested and sent to a camp; soon after her return to Russia her husband was arrested and executed; her surviving daughter was also arrested and sent to the camps.

Unpublished in Russia, she had few friends and little income. In 1941, in the desolate Tatar town of Yelabuga to which she had been evacuated, Tsvetaeva hanged herself. Soon afterwards her son was conscripted into the army and shot.

The extent of Tsvetaeva’s oeuvre and true stature emerged only in the 1970s. She wrote some dozen books of short poems, as many long poems, eight plays, and numerous prose works. Much of her work was written and first published in emigration.